Social media, journalism and wars: ‘Authenticity has replaced authority'

These, at least, were the main conclusions from a panel at the Web Summit conference in Dublin this morning, featuring representatives from Time, Vice News and News Corporation-owned social curation service Storyful.

“I’m not sure that the task of journalism has changed that much: we still send journalists to unearth stories and break news. But Twitter is our competition, and we have faced up to that reality,” said Matt McAllester, Europe editor for Time.

“All legacy media organisations in the US and UK have gone through that process. And some have not survived.”

While the panel shook their heads en masse when the phrase “citizen journalism” was mentioned, they admitted that on-the-spot witnesses are now as likely to be posting on social media as talking to a journalist.

“Twitter to us is a news source. Things break on Twitter,” said Kevin Sutcliffe, head of news programming, EU at Vice News.

“Now people can bypass us using a camera phone and a social network, and the means of production have been completely overturned,” added Mark Little, chief executive of Storyful. “Now everyone out there is a creator of content, and our job is more as managers of an overabundance of content.”

The panel stressed that not all of the old values have been swept away. “It’s really old-fashioned: can I find it out, is it true, can I stand by it? That level of trust is really important,” said Sutcliffe. “I’ve got a story, but does it stand up, is it true, what are my sources?”

“There will be two types of parallel journalism going on - the facts on the ground from people who are there, foreign correspondents, and people like us who filter,” said Little.

Some of the filters will be the same media organisations who employ on-the-ground correspondents, though. Time, for example, has a division focused on breaking news, which is deliberately kept separate from its foreign correspondents.

“We’ve hired a bunch of very young people in New York and Hong Kong and they’re essentially aggregating as a breaking news service: when anything appears from a reliable news organisation, quickly write two or three paragraphs and get it out there,“ he said.

“That takes care of the news and it doesn’t tax our correspondents. They do the premium you-can-only-get-it-here content that Vice News is [also] doing.”

However, Little was more critical of the idea of news organisations covering breaking news. “Social media has proved to us that the breaking news model is broken for good. It’s broken as a concept,” he said.

“As a business, it’s a really good business. But the concept that you, with the flashing ‘breaking news’ on the screen are going to be the first to break something is completely bullshit, because someone out there has witnessed it.”

He described Storyful’s approach, which focuses on finding those witnesses’ online posts, and bringing them to a wider audience. “The key thing for us is to find the first piece of content that will define a story: the video, the tweet… we have 40 journalists looking in real-time for the original source,” he said.

“For us the most important thing is who’s the person on the ground with the camera-phone standing there right now.. Authenticity has replaced authority as the new currency of this environment.”

Authenticity is sometimes a false currency, however: photographs claiming to show a bombing in one country may have been taken in another several months before, while false Twitter rumours can spread rapidly in the wake of a natural disaster or terrorist attack.

Little suggested that there’s increasingly a self-policing aspect to social media. “There’s never been a better way to spread a hoax than social media, but there’s never been a better fact-checking desk than social media,” he said.

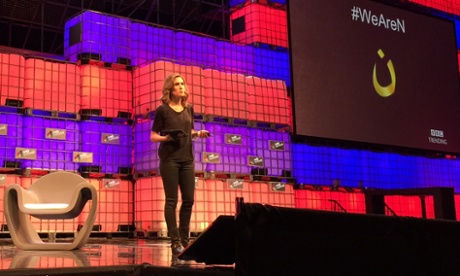

In an earlier session, Anne-Marie Tomchak, presenter and producer at BBC Trending, made a similar claim. “It’s not just journalists who are asking lots of questions about what’s being shared online,” she said. “Social media users have become really discerning about what they’re seeing.”

In the later session, the trio of journalists were optimistic about the appetite for hard news and foreign affairs among the “millennials” who are the most active demographic on social media, with Sutcliffe reiterating a claim that Vice executives have made regularly in recent months.

“It’s come out of a really interesting debate in heritage news, that young people were not interested in news, and they were not going to watch anything longer than two minutes online, probably featuring a cat,” he said.

“What we’ve found over the last six months, we’ve overturned the sense that there isn’t an interest from this age group for news, current affairs and the world. It’s enormous and it’s growing exponentially.”

McAllester suggested that 5-10 years ago “the orthodoxy was the world doesn’t care about foreign news” and agreed that modern, online outlets have put paid to the idea. “What Vice, BuzzFeed, Mashable and numerous startups are doing by hiring [foreign] correspondents and getting amazing traffic,” he said.

That’s incredibly encouraging to even an old brand like Time,” he said. “We all need competition. I absolutely see the BuzzFeed correspondent in the Middle East as competition… and that’s very encouraging.”

Sutcliffe suggested that the 24-hour television news cycle has become “slightly worn out”, suggesting that the news agenda in that world is driven by “everybody running in one direction after one story” rather than digging for new stories.

“What we’re commissioning is what we think is interesting and you should know about, and that can be anywhere,” he said. “We’ll do Ukraine and the big stories… but over there, that place that nobody’s bothering to go, that’s important too. We’re not chasing after other media organisations and their agenda.”

She cited the #WeAreN campaign, where people changed their avatars to a sign painted by ISIS members on Christians’ houses marking them out, in solidarity with those people, as well as the movement to share an image of executed journalist James Foley when he was alive, to crowd out images shared by Islamic State supporters of his beheading.

Tomchak also suggested that while Twitter tends to be the focus for these kinds of campaigns, as well as breaking news, mobile messaging apps like WhatsApp and FireChat have an important role to play.

“I truly believe that chat apps are and will increasingly become the place in which we will distribute our news, and the place in which we find stories, and the place in which we gather news,” she said. “Social media is a place for political, cultural and social change… and it is also one of the newest weapons in war,” she said.

In his session, Storiful’s Little warned that journalists must not underestimate the attempts by governments to subvert this role for social media.

“New forms of journalism will emerge. We’re in an arms race now from the NSA to the Chinese government, tying to close down freedom of expression, and use social media against itself,” he said. “We are on the opposite side.”

No comments:

Post a Comment